Stopping the Pendulum– the “Trafalgar Square” series by Cherine Fahd by Dr Nils Ohlsen

Stopping the pendulum – the “Trafalgar Square” series by Cherine Fahd

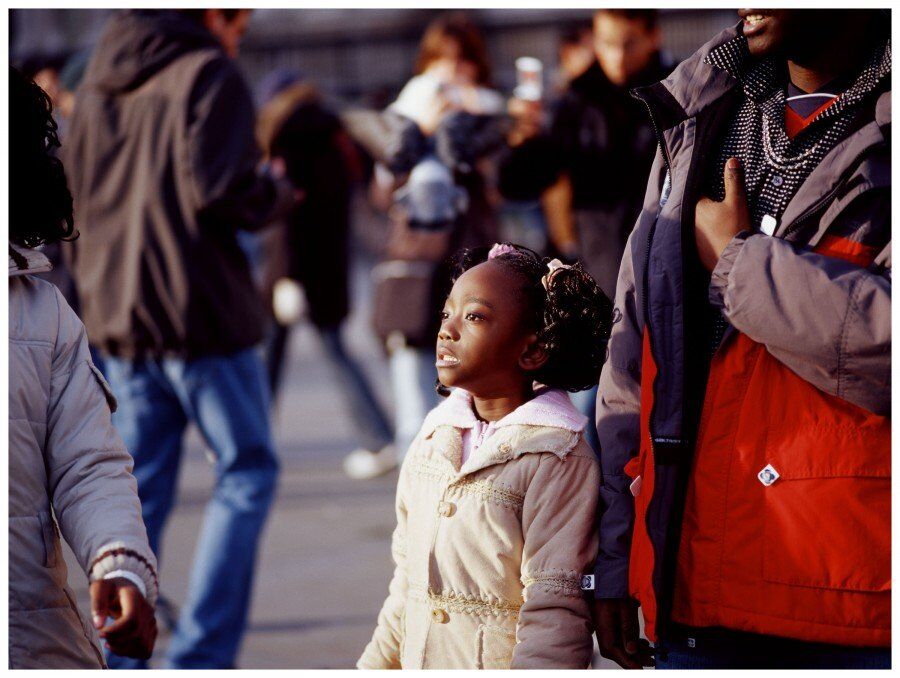

The photographs are quickly described: One or more people behind an iron railing and framed by two huge marble columns are focussed on from below at some distance. On closer inspection we can see that in her new series Cherine Fahd – globetrotter with Lebanese roots, born 1974 in Sydney – chose the portico of the London National Gallery as a frame for her figures. In spite of the identical set-up of the pictures it seems as if they were taken quite coincidentally: the columns are cut off at various heights, the angle of the camera varies and the perspective is occasionally shifted to the right or left side. Obviously, the artist does not want a fixed set-up with a central focus. Yet the composition is not an end in itself for the works. The people are determinant, framed by the architecture. Though appearing small between the columns of the time-honoured museum, they are the main motif of the photographs. These are definitely not portraits, however. Cherine Fahd’s artistic focus is not the individual person, but the documentation of actions, perceptions and emotions of nameless people within an urban context.

The artist makes up for deliberately forgoing formal strictness with human images of great naturalness and beauty. Involuntarily we try to imagine how the pictures were made. One can sense how the artist moved with her camera, searching, waiting and then taking sudden decisions whilst looking through the lens. She doesn’t stage her pictures, she reacts. The photographs are not the result of a well planned concept, but the reaction to events at a carefully chosen location. Uncertainty surrounds the protagonists and their behaviour until the picture is taken. The artist doesn’t tell any stories with her photographs, she wants to slow down the flow of time and to reveal the attitudes present. She seems to know exactly what distance she has to keep, to be able to capture her figures with the most natural expression.

This concept is typical for Cherine Fahd’s works of the past four years. Three series have been created since 2003, which suggest similar motivation: 2003/04 The Chosen, 2004/05 Looking Glass and 2005/06 the new series Trafalgar Square. In all three series she succeeds in capturing virtually archetypal situations which usually pass unnoticed within the homogeneity of urban daily life. Public places are her workspace and the background for nameless passers-by who either don’t notice the camera or who don’t mind it. In The Chosen Cherine Fahd watches individual people seeking refreshment under the fine spray of an obviously leaking water-pipe during a heat wave in Paris. A wet stone wall forms the background facing the camera. The water comes from an invisible source. In the photographs the unexpected fulfilment of the desire to cool down is distilled to moments of pure bliss. Cherine Fahd is able to capture natural attitudes and gestures which remind us of the religious ecstasy shown in baroque altar paintings. In the series Looking Glass the connecting element is not the location, but the technical manipulation of the pictures. Based on photographs of passers-by, which the artist shot in parks or pedestrian areas in Berlin, the distance from the subject enables an unfiltered view of everyday life. By subsequently applying very soft focus using a computer to everything except the central figures, pairs or small groups, Fahd makes them stand out from their continuum of time and space. This manipulation makes the photographs look highly artificial. Sometimes the pictures seem like scenes set up with modelling kit figures. It is as if the artist makes time stand still to intensify the existence of her chosen figures. As with The Chosen previously, a simple, open concept turns apparently coincidental and unspectacular situations to moments of beauty and emotional depth. In both cases the serial form has an advantage over the single photograph inasmuch as it offers any number of possibilities for extension. Seen together, the individual photographs determine the rhythm of the series.

In the new series Trafalgar Square the parallel fragments of the columns and the alternating dark and bright stripes form such a rhythm. Urban space here is not only background, but also stage. Compared with the previous series the distance to the figures has increased, whilst at the same time their range of action has been reduced: people are standing behind the railing, looking out. Because the photographs of the Trafalgar Square series look so alike at first glance, they invite us to compare them with each other even more than the other series did.

The photographs show tourists or art-loving Londoners gathering in the colonnade at the entrance about to enter the museum, or those, whose visit is over and who are now emerging from the distant world of old art into the hectic one outside. At the border between the quiet galleries with their historical works of art and the vibrating life in the street they pause, exposed, underneath the mighty portico above Trafalgar Square. They seem to gather themselves, breathe deeply, and reflect again on what they have just seen in the museum. They are confined within a narrow transit zone where changing light and sounds alter their perception. The pictures are captivating with their wealth of colour and emotion. The longer we look at them, the more we can detect differences between them and they display an almost picturesque attraction. Whilst in some pictures the scene is dipped in warm honey colours, the cold grey and blue notes of other photographs make one feel the chill of a late afternoon. A comparison shows how exactly the colours of the architecture – varying with the changing light of the day – correspond to the colour of an individual person’s clothing. Vertical stripes of light on the architecture, light bouncing off the window panes or shadowy areas of the colonnade emphasize the faces of the figures at the railing.

The form the series takes sensitises the viewer to body language, gestures and appearance of the individuals. Some figures are quietly looking out over the photographer into the distance, their heads slightly tilted. If you know Trafalgar Square you can guess what they see. In the middle of the square is Nelson’s Column, 185 feet high and crowned by the 17-foot bronze statue of the British admiral. The people in the photographs are probably looking at the victorious lord from their exposed vantage point. Others have their eyes closed and let the low afternoon sun shine in their faces. In others they are looking down – leaning on the railing – at the probably busy square in front of the museum. To see and be seen are the two poles between which the relationship of the photographer, the person in the photograph and the invisible figure on the column unfolds.

In her pictures Cherine Fahd seeks out moments experienced more or less consciously between two levels of reality leading to different representations and perceptions of the self. To this end she chooses a perspective and composition inevitably reminiscent of other works in art history. There are countless examples of sculptures standing in niches or wall paintings being framed by two huge columns. Even in portraits the column has been popular since the Renaissance for prestigious iconography. Frescos like Giustiniana Giustinian and her nurse by Veronese from 1560/61 (Cf. Ill. 1) are similarly composed to the Trafalgar Square series. Whilst this Renaissance painter emphasizes the prestigious position of the lady of the house behind the balustrade in his mural by painting from a very low point of view, Rembrandt van Rijn’s famous work Ecce Homo from 1655 has a different effect (Cf. Ill. 2). Here the viewer is not forced into the position of an obeisant subject, but becomes the judge of Christ presented on an elevated stage. Both artists integrate the viewer as an active part of their image concept.

Although Cherine Fahd uses the same concept as the two Renaissance artists, the viewer remains a neutral observer, since there is no direct eye contact with the person in the photograph. Edouard Manet gives the viewer a similar role in his painting The Balcony (Cf. Ill. 3) from 1868/69. Framed by two tall window shutters Manet presents his figures on a balcony behind a wrought iron railing. By choosing a place bordering private and public he succeeds in describing how private behaviour can become a pose.

In Cherine Fahd’s Trafalgar Square series the subject is not on the border between private and public but between an attitude intended for outward appearance and a rare moment of “self-absorption”. Like Manet she singles out individuals from the anonymous mass and turns them into a timeless allegorie reélle for the real, unmasked self. An aura of silence seems to envelop them. Something best described as an “in-between-situation” is at the centre of the Trafalgar Square series, situations disconnecting individual people from their purposeful, rational flow of actions and giving them the dignity of something timeless, sublime. The artist looks for these precious moments between the columns and she finds them, because she can “listen” with her camera. With the delicate, unobtrusive note of her photographs Cherine Fahd explores the possibilities of making emotions visible within the tension between the individual and the urban context. Thus, she documents a realm as mysterious as it is familiar. In a figurative sense she succeeds in capturing for a split second the moment between the two swings of a pendulum and to transform it into a timeless picture.

Dr Nils Ohlsen