Summertime by Linda Michael

Summertime

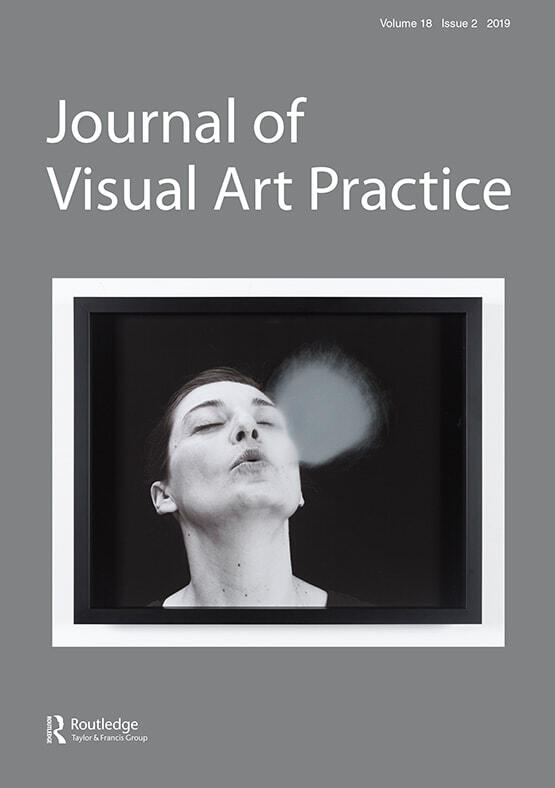

Cherine Fahd’s photographs from her series The Chosen (2003-04) each picture a person cooling off underneath a water sprinkler in the warm sun, in front of a golden sandstone wall. On what must have been a miserable day in Melbourne, my initial response to these photographs was to daydream of Sydney sun, surf and sandstone. Though based in recognition, my nostalgia was slowly undermined by a realisation that the place in the photographs was in fact unfamiliar. I noticed the people’s shoes. In Sydney no-one would be wearing them. And I could not place the iron rings and bars built into the wall. I later learnt that the actual location was Paris, during a heatwave.

Depicting people of varying ages, races and sizes, the photographs also made me imagine a time that seems increasingly distant. When everyone was equal under the sun. Everyone seemed equal in these photographs, united in a summertime abandonment to warmth and water, subject only to a dispassionate sun. I wished that we could all exist in such an undifferentiated space.

But the title The Chosen suggested this equality might be an illusion. The sun may not discriminate, but the photographer did. She chose to depict only one person in each photograph, though the location was public, and probably crowded. The people seem to have been chosen because they are totally in the moment, alone, within themselves. The very act of choosing creates or intensifies this look. As Fahd has written: ‘As the chooser, I had to be invisible; I couldn’t let them see me seeing them. It is this difference between knowing you are being photographed and not knowing, that is documented in The Chosen’.1

Paradoxically, the chosen people could potentially be replaced by anyone else as the very result of their unselfconsciousness, as this somehow taps into what is shared.

Fahd sought to capture the emotion she saw in people looking up at church windows or paintings: ‘it was under the Sistine Chapel that I recognised that God was not the bearded man that was flying above me, but the intensity of feeling, of wonder, that was experienced by all those seated under it.’2

Many of the people photographed here face upwards too, with arms held out from the body, often with eyes closed and mouth open. They are oriented towards the light as surely as sunflowers. The freezing of this movement at its climax creates a particular intensity – the people seem truly to surrender to the moment they are in. The isolation of each figure and its shadow within a shallow space further concentrate this corporeal drama. In resonance with the redemptive theme suggested by the title, the ‘chosen’ mimic the demeanour of worshipping or ecstatic figures in religious art. Through a felicitous orchestration of light, Fahd turns their receptivity to the sensual pleasures of water and sun into a receptivity to ‘divine’ light.

The photographs show this surrender to something higher as grounded in the body, concurring with a recent definition of feeling by neurologist Antonio Damasio as ‘the perception of a certain state of the body along with the perception of a certain mode of thinking’.3 The people look as if they feel from head to toe; unselfconscious but internally aware, they are suspended in a moment of total awareness of body-mind.

Georges Bataille defined the sacred as ‘only a privileged moment of communal unity, a moment of the convulsive communication of what is ordinarily stifled’.4 This group of photographs points to such a moment, by uncovering feeling-bodies in states of joy, exhaustion, pain or rapture. They are far from war photographs, but like them seem to expose a kind of expressive limit at which unity, not separation, is important. So rather than registering the inner world of an individual, the emotional body language is shown as repeatable and marks an act of fusion with community.

These photographs lure us by a kind of magic whereby a simple everyday act is both just itself and the vehicle for meaning. Different layers of reality and illusion cohere in images of everyday reality reconstructed through Fahd’s photographic eye. Actual light is turned into metaphorical light, immobile bodies move our minds. The Chosen series could make me nostalgic, or idealistic for some form of redemption from the material world it documents, because at the same time it gestures towards a promise of salvation.

Linda Michael

Melbourne, 2004

1 Cherine Fahd, artist notes, 2004.

2 Ibid.

3 Antonio Damasio, Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow and the Feeling Brain, Harcourt, 2004, p. 86.

4 George Bataille, Visions of Excess: Selected Writings,